GERD in children

Symptoms of gastroesophageal reflux disease in children are divided into two groups: those associated with the gastrointestinal tract (esophageal) and those not associated with the gastrointestinal tract (extraesophageal). In infants and preschool-age patients, the main clinical manifestations of GERD are vomiting (rarely streaked with blood), regurgitation, and insufficient weight gain. In some cases, disturbances in the functioning of the respiratory system occur, leading to respiratory arrest or sudden death. In adolescents and children of the older age group, the picture of gastrointestinal disorders is more clearly visible, heartburn and dysphagia are observed. Regardless of age, GERD may cause weather dependence, insomnia, headaches and emotional instability.

Esophageal manifestations are a direct consequence of the impact of refluxed contents on the wall of the esophagus. The primary and most common (but not obligatory) symptom is heartburn. Subsequently, regurgitation and belching of sour or bitter foods occur. Many patients have a “wet spot” symptom, in which a whitish mark remains on the pillow after sleep. The cause of its development is hypersalivation, which is characteristic of impaired motility of the cardiac esophagus. Odynophagia (pain behind the sternum while eating) and dysphagia, manifested by a sensation of a lump in the chest, may be observed. Sometimes there are no clinical manifestations of gastroesophageal reflux; changes are revealed only during instrumental examination. The opposite option is also possible when, with severe clinical GERD, endoscopic signs of the disease cannot be detected.

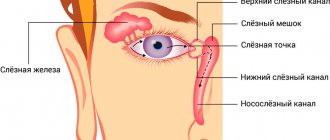

All extraesophageal symptoms of gastroesophageal disease in children are divided into groups. Most often, GERD is accompanied by bronchopulmonary manifestations (up to 80% of cases). Bronchial asthma and broncho-obstructive syndrome are usually observed, accompanied by paroxysmal cough or shortness of breath after eating and at night. Often these symptoms are combined with belching and heartburn. With adequate treatment of GERD, bronchial obstruction decreases or completely disappears. Typical otolaryngological symptoms include sensations of tickling and food stuck in the throat, hoarseness of the voice, a feeling of pressure in the neck and upper chest, ear pain and coughing that is not dependent on food. Cardiac manifestations of GERD are caused by the esophagocardial reflex, which can cause sinus arrhythmias, extrasystoles and the phenomenon of slowing intraatrial conduction - an increase in the PQ interval. Odontogenic symptoms of GERD include the formation of erosions on tooth enamel.

Gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) is a fairly common gastroenterological disease in children, including very young children. However, gastroenterologists, and especially pediatricians, do not always take this condition into account in the differential diagnosis of chest pain, abdominal pain, repeated vomiting, regurgitation and many other symptoms, including extra-abdominal ones [1].

Gastroesophageal reflux (GER) in children most often occurs when the lower gastroesophageal sphincter is immature, which is manifested by its periodic relaxation and retrograde flow of gastric contents into the esophagus. The following GER options are distinguished:

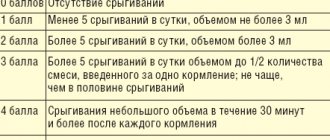

1. Physiological (functional). The frequency of reflux episodes decreases with age, but their severity increases. In the first 3-4 months of life, 65-70% experience at least 1 episode of excessive regurgitation (vomiting) per day after feeding. This is due to the immaturity of the lower esophageal sphincter, which matures by 2-4 months of life. Such children do not have factors predisposing to pathological reflux (short esophagus, pyloric hypertrophy, intracranial hemorrhages, etc.), growth and development do not suffer. In most children, by the age of one year, after switching to adult food (thicker) and a stable vertical position, repeated episodes of regurgitation and vomiting are successfully completed. The presence of these disorders at 1.5 years of age indicates a high probability of pathological GER [2]. The definition of GER as physiological or pathological is based on several provisions. Firstly, the presence of characteristic complications (dysphagia, odynophagia, chest pain, esophagitis, strictures, developmental disorders, etc.) and, secondly, a study of the frequency and height of reflux, which is determined by the results of 24-hour pH measurements in the esophagus [3].

2. Pathological GER = gastroesophageal reflux disease.

3. Secondary GER (obstruction of the gastric outflow tract).

The true incidence of GERD in the population is unknown.

Several factors contribute to the development of pathological GER in children, compared to adults. Pathological childbirth often leads to increased intracranial pressure and mild vomiting. Infants' food is predominantly liquid, they spend a lot of time lying on their backs, the stomach volume is relatively small, and a large volume of liquid food is required to replenish the physiological need for energy (calories). The angle between the axis of the esophagus and the axis of the stomach (His angle) in infants and young children approaches 1800, and in adults - 900. The esophagus is short and relatively wider than in adults. Peristalsis of the esophagus in premature infants is sluggish, clearance of the esophagus is difficult. They are also characterized by delayed gastric emptying. The development of GERD is promoted by hydrochloric acid and gastric juice pepsin, lysolecithin, trypsin and bile acids. Sanogenetic factors are the antireflux barrier function of the gastroesophageal junction and lower esophageal sphincter, esophageal clearance (cleansing), resistance of the esophageal mucosa, timely evacuation of gastric contents, control of the acid-forming function of the stomach.

Predisposition to the development of GERD is:

- obesity (increases intra-abdominal pressure). Weight loss itself leads to improvement in GERD. Loss of body weight, traditionally considered a sign of GERD, is observed only in erosive esophagitis with anemia, and with strictures of the esophagus.

- binge eating;

- carbonated drinks, sour foods;

- habit of lying down after eating;

- squatting;

- slouch;

- increased intra-abdominal pressure;

- food allergies;

- delayed gastric emptying;

- smoking;

- alcohol;

- some medications that reduce the tone of the lower esophageal sphincter (theophylline, diazepam, etc.).

The clinical picture of GERD is varied. Young children do not have the typical symptoms of GERD. At this age, the disease is manifested by repeated regurgitation and vomiting, crying during feeding, poor sleep, pallor, decreased appetite, retarded growth and weight, persistent thrush, repeated otitis and laryngitis, episodes of apnea, tachy- or bradycardia.

In older patients, abdominal and extra-abdominal symptoms are distinguished.

Abdominal symptoms:

- heartburn. Retrosternal burning sensation extending upward from the xiphoid process. The result of the prolonged presence of acidic gastric contents in the esophagus.

- feeling of acid in the mouth

- belching sour or airy

- pain behind the sternum, at the edge of the xiphoid process, in the epigastrium. Pain with GERD can be of a different nature (burning, pressing, paroxysmal, constant or short-lived, associated with eating, intensified in a horizontal position and when bending over). Possible irradiation to the arm, jaw, back. Often the vegetative component is clearly registered: sweating, trembling in the body.

- hiccups

- vomit

- feeling of early satiety

- heaviness in the stomach after eating

- flatulence

- d isphagia

- odynophagia

- bitterness in the mouth.

Typical dental manifestations of GERD: exfoliative cheilitis, seizures, burning sensation of the tongue, coating of the posterior 2/3 of the dorsum of the tongue, desquamative glossitis, caries of the medial surface of the median incisors (usually the upper ones), rapid formation of tartar, verrucous leukoplakia, gingivitis, periodontitis.

Extra-abdominal symptoms:

- pulmonary (bronchial obstruction, chronic cough, especially at night, apnea, cyanosis, pallor, recurrent pneumonia, interstitial pneumonia and pulmonary fibrosis);

- cardiac (angina-like pain, palpitations, shortness of breath, increased blood pressure);

- otolaryngological (hoarse voice, rough barking cough, feeling of a lump in the throat, recurrent subglottic laryngitis, granulomas and/or ulcers of the vocal cords, pharyngitis, laryngeal neoplasms, recurrent otitis media, chronic rhinitis).

Differential diagnosis is carried out depending on the patient’s age, severity of symptoms and the presence of additional signs with all syndromes of impaired gastric evacuation (pyloric hypertrophy, duodenal stenosis), tracheoesophageal fistula, intestinal malrotation, esophagitis, food allergies and intolerance to food components, acute and chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer, diaphragmatic hernia, irritable bowel syndrome, etc.

The diagnosis of GERD can be confirmed by many methods, the most common and acceptable in pediatric practice are:

Long-term esophageal pH-metry. To do this, the pH-sensitive electrode must be located 87% of the distance from the nose to the lower esophageal sphincter. This is determined by the formula: (body length x 0.252 + 5 cm) x 0.87. Transnasal insertion of the electrode is preceded by local application of lidocaine gel. The position of the probe is controlled echographically or radiographically. Next, an observation protocol is kept, where periods of eating, drinking, physical activity, and vomiting are noted. Starting from the 2nd month of life, the duration of reflux more than 10% of the observation time and/or above the lower quarter of the esophagus speaks in favor of pathological GER. Or a decrease in pH<4 in the lumen of the esophagus for more than 1 hour is considered pathological reflux. Monitoring pH in the esophagus allows us to identify distal and proximal GER, its frequency and severity, connection with periods of apnea, broncho-obstruction, tachycardia, etc., and distribute medications.

Manometry is a sensitive and highly specific method. Allows you to evaluate the motility of the esophagus and the tone of the lower esophageal sphincter.

Esophagogastroduodenoscopy directly visualizes the condition of the esophageal mucosa, detects strictures, and allows obtaining a biopsy specimen.

X-ray studies are designed to detect developmental anomalies, hiatal hernia, and the rate of gastric emptying.

Scintigraphy is designed not so much to diagnose reflux as to detect aspiration into the lungs.

Treatment for GERD is long-term. The goal of therapy is to reduce the frequency of reflux episodes, their duration, and reduce the acidity of the refluxant. But in some patients, the refluxant contains a large amount of duodenal juice, bile acids, and trypsin. The acidity of the esophageal contents does not change, but the symptoms of GERD remain. Such patients require consultation with a surgeon.

Treatment of GERD begins with changes in diet, nutrition, and normalization of body weight. In infants, food thickeners (Nestergel), a vertical position after meals, a decrease in the volume of feeding with an increase in the frequency of feedings are used.

Antacids are prescribed in a dose of 0.15-0.25 mg/kg per dose 1 hour after meals or “on demand”. Prokinetics (Cisapride 0.2 mg/kg 2-3 times or Metaclopramide 0.1 mg/kg 3-4 times) can cause life-threatening cardiac arrhythmias or extrapyramidal disorders.

H2 receptor antagonists (see Table 1) do not reduce the frequency of reflux, but reduce the concentration of acid in the refluxant. Their effectiveness is the same when given in equivalent doses. H2 receptor antagonists are most justified in children with non-erosive esophagitis.

The prescription of proton pump blockers is justified in children with chronic pulmonary pathology and neurological disorders. They are prescribed in the morning with the first meal.

V.M. Delyagin1, D.V. Fadeeva2, A.V. Myzin1

1Federal State Institution Federal Scientific and Clinical Center for Pediatric Hematology, Oncology, Immunology, Moscow;

2Regional Children's Clinical Hospital, St. Petersburg.

Delyagin Vasily Mikhailovich - Professor of the Federal Scientific and Clinical Center for Pediatric Hematology, Oncology, Immunology

Literature:

1. Schwarz S., Hebra A. Gastroesophageal Reflux. // eMedicine, Last Updated: January 18, 2008. https://www.emedicine.com/ped/topic1177.htm

2. Gold B. Gastroesophageal reflux disease: could intervention in childhood reduce the risk of later complications? // American Journal of Medicine, 2004. - v. 117. - Suppl. 5A. - 23S-29S.

3. Illing S., Claβen M. Klinikleitfaden Pädiatrie. / Urban & Fischer, Munich, 2000. - ss. 477, 479 - 480.

What other methods are used for examination?

Additional information about the condition of the urinary organs in children with VUR can be obtained by intravenous urography, bladder function testing (urodynamic study), cystoscopy and laboratory tests. Kidney function is determined based on radioisotope studies (nephroscintigraphy). As a result of these studies, refluxes are further divided into primary (pathology of the ureteric orifice) and secondary, caused by inflammation and increased pressure in the bladder.

What determines the results of endoscopic treatment?

The method has many technical nuances, so the results of its application vary significantly. Cure after one endoscopic procedure ranges from 25 to 95%, and the final results of treatment in different hands range from 40 to 97%. More reliable results were obtained when using non-absorbable pastes - Teflon, Deflux, Dam+. The best results were observed with: primary procedures, low-grade reflux, the absence of gross anomalies of the ureteric orifice and bladder pathology.